Wednesday, 31 December 2014

Plastic Photovoltaic Cell

I have had to wait a while to play with the cell, but now that I have, I am super impressed.

The cell came from http://www.plasticphotovoltaics.org. Their website says that the Department of Energy Conversion and Storage at the Technical University of Denmark is behind this little gem.

I have tested the cell both indoors (0.67V) and outside in full sunlight (7.56V) and I must say that I am very impressed with the freeOPV. By the way, mine is version 2014 – V2.0 – A1 25.3. The website indicates that I should be able to get around 8V from the 16 strips. I’m getting close to that, so … woot!

Okay, so … what am I going to do with my freeOPV? Well, obviously it has to be something that is in keeping with the renewable energy/green principles of an organic solar cell.

I have a small vegetable patch that is about 3m x 3m sitting next to a 8m x 3m shed. The guttering on the shed feeds in to a 10,000 ltr water tank.. What I would like to do is to make the water usage of the vegetable patch as efficient as I can.

The plan is to make a watering system that responds to the moisture level detected in the soil, turning the water on for a pre-set amount of time when the moisture level falls below a set value.

I will need to embed a hygrometer in the garden that will periodically take a moisture level reading. The Arduino will read the moisture level and compare it to a stored moisture level value. If the moisture level is below the stored value, the pump is turned on for a set amount of time (say 5 minutes). If the moisture level is equal to or above the stored value, the pump remains turned off.

I’ve calculated that the roof of the shed is approximately 24m2. I’ve also calculated the average rainfall (mm) in my area and factored in a water collection efficiency value (0.9).

Area x Average Annual Rainfall x collection co-efficient = Litres Collected Per Annum.

For my system, this means an average annual rainfall of something over 14,000 litres per annum. This gives me a daily water consumption rate of around 38 litres.

Now for some more calculations. Some horticulturalists give an average of 1 inch of water per week or 630 gallons per 1,000 square feet). Damn … conversion time. That’s equivalent to 2384.80942 litres per 304 square meters … roughly 8 litres per square meter, per week.

My garden is 9 square meters, so that would mean that I need to use 70.5 litres per week … or 10.08 litres per day. Right … so I have almost 4 times as much water as my vegetable patch will use.

There are other factors to consider, different vegetable crops require different water levels at different times in their development … plus! If I use water efficient planting (using mulch and increasing the humus in the soil, I need even less water input.

Well, for the sake of this experiment, let’s keep things simple.

If the water level drops down below 10% moisture content, turn the pump on for 5 minutes.

I’m expecting that the pump will not come on all that often and it shouldn’t come on at all on rainy days..

Of course, I will want to be able to log in to the vegetable patch, night or day, from ANYWHERE on the globe and get mission critical information pumped straight to my smart-phone. I want to be interrupted while having a highly charged and pressure lunch with senior business partners with information on the drinking habits of my legumes. Clearly, I will need to embed some Wi-Fi capability into my circuit so that I can interrupt Mr CEO while I water my dinner (more likely I will get a beep while in a job interview).

An Arduino Hygrometer module comes in at around $2.00 on eBay. I’m not sure about the pump control yet, so I can’t comment on cost, but lets say about $20

Wednesday, 3 December 2014

Hiatus – Moving again

Well folks, it’s time for me to move on. I’m in the process of packing up my flat and getting ready to move interstate. My job in Tasmania has ended and I am moving to Victoria.

There are a couple of things that this move will mean to me, not lest of which is that I will be living with my wife and daughter again after more than a year of only seeing them on weekends when I fly back home. The whole interstate commute is a pain in the arse and, it turns out, very costly.

Probably the big thing that this move will mean, in terms of pursuing my hobbies, is that I will have better access to stuff and the postal service to Victoria is much better than to Tasmania (it doesn’t have to traverse the “Bass-Triangle”).

I will have more space to work and tinker. At the moment, my workspace is limited to a corner of a desk in a small lounge-room with fairly poor lighting. In our house, I have a room that is dedicated to my hobbies (and work) with a separate desk for electronics. I also have a large workshop in the back yard for larger tinkering's. I still don’t really have space for my aluminium recycling/melting, but that is a very small price to pay. I might get an electric furnace at some later stage and do some re-invention.

Another aspect of the move that I am quite looking forward to is that I will be able to go along to electronics clubs and makers clubs to get more ideas and to share some of mine.

The upshot of this is that I’m shutting up shop until after the 2015 New Year.

Have a wonderful, happy and safe time until then. I have enjoyed all of the tinkering, thinking, inventing and practicing that has gone into making these articles and it is my firm commitment to come back and do it again in the New Year.

Oh, and in case you are interested, one of the first projects that I am going to work on, in the new year, is a 20 LED Charlieplexed display.

Monday, 17 November 2014

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 11 – Light Input Controlling Sound Output

This is the final Freetronics 11 – Experimenters Kit tutorial. The other 10 tutorials have been covered and, I’m please to say, I have now completed all 11 tutorials with the ATTiny85.

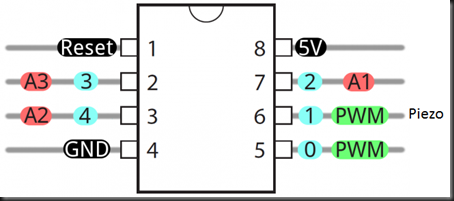

This tutorial makes use of the Freetronics Light module (a light detecting resistor or LDR) with the Freetronics Sound module (a piezo electric module). The light level is read by the analog LDR and the light level value is passed as a tone to the piezo.

Once again, we are using a web sourced tone function that makes use of the ATTiny85 timers to produce an output tone value. This time, however, we are not using predefined wave cycle values, but using analog light level values to drive the tone.

The Piezo is connected on pin 1 (ATTiny85 pin 6), while the LDR is connected on A2 (ATTiny85 pin 3).

The LDR also connects VCC to the positive rail and GND to the negative rail.

The modified sketch:

/* Tutorial 11: Light Input Controlling Sound Output */

int piezo = 1;

int lightLevel = 0;

int duration = 300;

void setup()

{

pinMode(piezo, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

lightLevel = analogRead(A2);

TinyTone(lightLevel, 4, duration);

}

void TinyTone(unsigned char divisor, unsigned char octave, unsigned long duration)

{

TCCR1 = 0x90 | (8-octave); // for 1MHz clock

OCR1C = divisor-1; // set the OCR

delay(duration);

TCCR1 = 0x90; // stop the counter

}

I believe that TCCR1 and OCR1C both point to pin 1 (but I’d have to research that a little to make sure). Reason tells me that this is so … reason and I are not always particularly good friends.

It would be nice to reduce the delay so that the tones are more smooth, it would be kinda like a light driven theramin.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

Friday, 14 November 2014

AVRDUDE – Pagel and BS2 error

Apparently, you need to correct the configuration problems and then everything will be fine. It is.

- Go to your Arduino IDE installation folder (something like C:\Program Files (x86)\arduino-1.0.4\hardware\tools\avr\etc.

- Before you do anything … make a backup of the file avrdude.conf

- Open the avrdude.conf file in a text editor

- locate the ATTiny85 section in the file

- locate the chip_erase_delay = 4500; line

- add the following two lines below this:

- pagel = 0xB3;

bs2 = 0xB4; - locate the memory=”lock” keyword in the ATTiny85 section

- replace this section with the following (copy and paste)

size = 1;

write = "1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 x x x x x",

"x x x x x x x x 1 1 i i i i i i";

read = "0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0",

"0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 o o o o o o o o";

min_write_delay = 9000;

max_write_delay = 9000;

;

Do the same for the ATTiny84 section.

You will need to restart the IDE for this to be affected.

After this, you need to

- Connect the ATTiny85 to the Arduino using your favourite ICSP

- load the sketch into the IDE

- Select the ATTiny85 board in the IDE

- Select Arduino as ISP in the IDE

- Upload your sketch to the ATTiny85.

I have now tested the abovementioned fix and the error message has now gone away. To test this, I loaded the sketch from Tutorial 10, compiled and then uploaded it to the ATTiny85 with the following, successful, result.

As you can see, the Pagel and BS2 error messages have gone … YAY! Thank you Wiki Page!

After uploading the sketch to the ATTiny85, I dropped the ATTiny85 chip into the circuit and powered it up, again, success. The circuit does what it’s supposed to do.

All in all, happy camper time.

Thursday, 13 November 2014

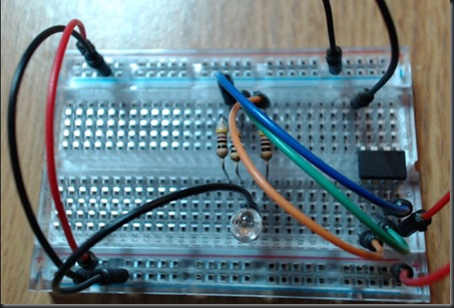

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 10 – Detecting Knocks and Vibration

This tutorial in it’s original form sends the detection of knocks and vibrations from the Freetronics ”Sound” module to the serial monitor. As we don’t have access to a serial monitor from the ATTiny85, instead we are going straight to the extended tutorial, monitoring our knocks and vibrations with an LED.

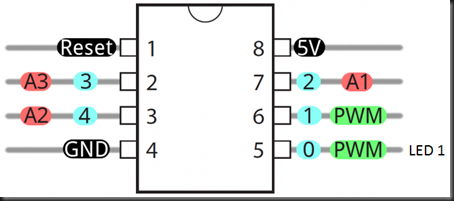

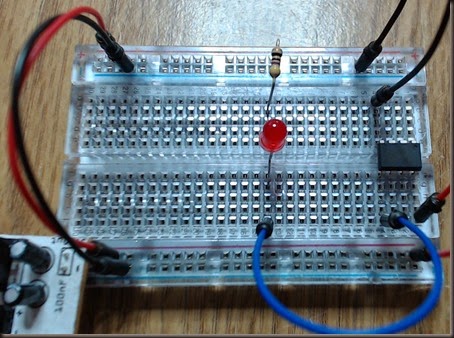

For this tutorial, the Piezo (Sound module) is connected on A1 (ATTiny85 pin 7) and an LED is connected to 0 (ATTiny85 pin 5).

The Piezo is read using the analogRead Arduino function and, when the analog value read from the Piezo is > 5, it will light up our LED (with a pull down resistor).

/* Project 10: Detecting Vibrations and Knocks */

int knock = 0;

void setup()

{

pinMode(0, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

knock = analogRead(A1);

if(knock>5)

{

digitalWrite(0, HIGH);

delay(300);

digitalWrite(0, LOW);

}

}

The sketch is pretty straight forward … the variable knock is assigned the value of analogRead and, if it’s value is > 5 the ATTiny85 turns the LED on with digitalWrite, then waits 300 milliseconds, and then turns the LED off again with digitalWrite.

You can see from the above image that the wiring is pretty straight forward. Top right of the breadboard is the 5V regulator. The ATTiny85 was programmed using the ATTiny85 ICSP.

This is the 10th Freetronics Experimenters Kit tutorial that I’ve converted to the ATTiny85.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

Thursday, 6 November 2014

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 9 – Making Sounds

While this looked like a fairly simple tutorial on the face of it, it was actually a bit more difficult.

The main problem that I encountered was that the tone() function is not supported by the ATTiny85 core, so I had to do a bit of hunting around to find an equivalent method for the ATTiny85. As I expected, others had come across this same problem and had already developed a solution for it.

Two of the solutions that I tried (arduino-tiny library and a beep function) were both unsuccessful. Both produced cricket sounds (probably because the timing was wrong). However, I found Simple Tones for ATtiny that produces a nice scale and didn’t cause me too many other problems.

The connection from the ATTiny85 to the Piezo is very simple. Connect Pin 1 of the ATTiny85 to either pin of the piezo (it isn’t polarised). Connect GND to the other pin of the piezo.

Here is the sketch from the Technoblogy article referred to above (Simple Tones for ATTiny).

/* TinyTone for ATtiny85 */

// Notes

const int Note_C = 239;

const int Note_CS = 225;

const int Note_D = 213;

const int Note_DS = 201;

const int Note_E = 190;

const int Note_F = 179;

const int Note_FS = 169;

const int Note_G = 159;

const int Note_GS = 150;

const int Note_A = 142;

const int Note_AS = 134;

const int Note_B = 127;

int Speaker = 1;

void setup()

{

pinMode(Speaker, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

playTune();

delay(300);

}

void TinyTone(unsigned char divisor, unsigned char octave, unsigned long duration)

{

TCCR1 = 0x90 | (8-octave); // for 1MHz clock

// TCCR1 = 0x90 | (11-octave); // for 8MHz clock

OCR1C = divisor-1; // set the OCR

delay(duration);

TCCR1 = 0x90; // stop the counter

}

// Play a scale

void playTune(void)

{

TinyTone(Note_C, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_D, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_E, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_F, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_G, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_A, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_B, 4, 500);

TinyTone(Note_C, 5, 500);

}

This sketch works just dandy, straight out of the box. Nice work Technoblogy, nice work indeed.

I need to do some more research to find out how I can get the tone() function from the arduino-tiny library to work satisfactorily, but for now, the above sketch serves my purpose.

Well, that concludes Tutorial 9. Enjoy. Once again, 9V to 5V Regulator and ATTiny85 ICSP were used to make this tutorial circuit.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

Tuesday, 4 November 2014

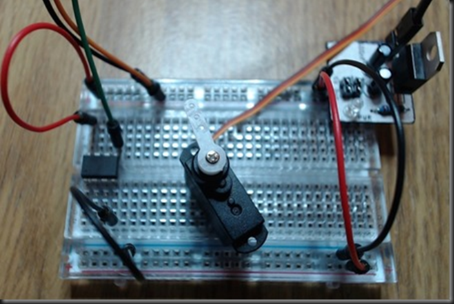

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 6 – Making Things Move With Servos

The Freetronics Tutorial 6 replaces the LED and Resistor connection on pin 11 of the Freetronics 11 with the data connection to a simple servo.

The ATTiny85 version does the same thing … not really much sense reinventing the wheel, huh?

As we learn with Tutorial 7, there are three PWM pins on the ATTiny85 to choose from. I went with the easiest and most convenient … our old friend, pin 0.

If you use the sketch from Tutorial 5 in the Freetronics Tutorial with a servo instead of an LED, then this sketch works admirably.

// Tutorial 6: Making things move with servos

int led = 0;

int brightness = 0;

int delayTime = 10;

void setup()

{

pinMode(led, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

while(brightness < 255)

{

analogWrite(led, brightness);

delay(delayTime);

brightness++;

}

while(brightness > 0)

{

analogWrite(led, brightness);

delay(delayTime);

brightness--;

}

}

Of course, I’m using the ++ and – incrementing function rather than brightness = brightness + 1; and brightness = brightness –1; because I think that it looks better, but that’s just me. Let the spirit guide you in your decision …

The green jumper connects from ATTiny85 pin 0 to the yellow connector on the servo, Red connects to Orange on the Servo from the 5V rail and the black jumper connects the brown servo connection to GND.

Here’s a short video of the action.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

Monday, 3 November 2014

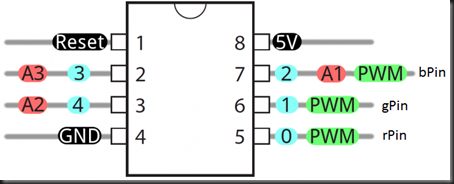

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 7 – RGB LED

I was playing around looking at the information at hand on the ATTiny85 PWM and I thought that there were only 2 PWM capable pins on the chip … apparently, I was wrong, there are three. PB0, PB1 and PB2 are all PWM. Until I realised that, I was toying with the idea of software based PWM. There are some pretty good articles, tutorials and pages relating to software PWM, so I’ll probably get around to playing with it, some other time.

In the meantime. I had another look over the Freetronics Tutorial #7 – RGB LED and I decided that the code was a little clunky. The RGB values all jump to their random values and there is a lot of blinking … that’s OK if that’s what you want. Anyway, I had a quick play and decided to make the values rise from 0 to their random value and then back down to 0 so that they fade in and out. It’s still a little inelegant, but for the sake of a decent tutorial, I thought that this would be fairly useful.

My code is as follows

//Tutorial 7: RGB LED *** EXTENDED

int rPin = 0;

int gPin = 1;

int bPin = 2;

void setup()

{

pinMode(rPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(gPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(bPin, OUTPUT);

analogWrite(bPin, random(0, 255));

analogWrite(gPin, random(0, 255));

analogWrite(rPin, random(0, 255));

delay(500);

}

void loop()

{

upDown(random(0,255), random(0,255), random(0,255));

delay(500);

}

void upDown(int r, int g, int b)

{

//bring the colours up

int rVal, gVal, bVal = 0;

for(int rVal = 0; rVal < r; rVal++)

{

analogWrite(rPin, rVal);

delay(10);

}

for(int gVal = 0; gVal < g; gVal++)

{

analogWrite(gPin, gVal);

delay(10);

}

for(int bVal = 0; bVal < b; bVal++)

{

analogWrite(bPin, bVal);

delay(10);

}

// return to 0

while(rVal>0)

{

rVal--;

analogWrite(rPin, rVal);

}

while(gVal>0)

{

gVal--;

analogWrite(gPin, gVal);

}

while(bVal>0)

{

bVal--;

analogWrite(bPin, bVal);

}

}

This is still fairly close to the original, with an upDown function that fades each colour in and then all of them out again.

I used my ATTiny85 ICSP to program the ATTiny85 and the 9V to 5V power regulator to supply the solderless bread board.

As you can see, there isn’t anything outside of the Arduino core being used in the code, and the wiring is very straight forward. The layout is as per the Freetronics tutorial (more or less … I’ve added a jumper from the top to bottom rails).

Here is how it looks when it’s running. Bear in mind that the cycle uses a random RGB value and splits it up, so it *should* be different for every cycle.

Well … it’s now well past my bed-time, so I’m calling it a night.

Have fun ATTiny85ers!

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

ATTiny85 – Tutorial 5 – Dimming LED using PWM

This tutorial is a very simple conversion from ATMEGA328P to ATTiny85, there is only one pin involved in producing output, so we only need to change from pin 11 to pin 0. On the ATTiny85, there are three hardware PWM pins … pin 0, pin 1 and pin2 , so it’s simply a matter of switching over to Pin 0 and away we go.

I’ve changed the sketch for personal taste (and I think, efficiency), you’re free to use the Freetronics version of the code if you like … it’s no great shakes on something this small.

/* project 5: Controlling LED brightness with PWM */

int led = 0;

int brightness = 0;

int delayTime = 10;

void setup()

{

pinMode(led, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

while (brightness < 255)

{

analogWrite(led, brightness);

delay(delayTime);

brightness++;

}

while (brightness > 0)

{

analogWrite(led, brightness);

delay(delayTime);

brightness--;

}

}

As you will see from the following image, there isn’t much to the wiring for this project.

And here’s the circuit running through it’s light/dim wizardry.

Once again, I’m using my ATTiny85 ICSP to program the ATTiny85 using the Arduino UNO and my 9V to 5V power regulator to supply 5V to the circuit.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

ATX Lab Power Supply – Planning Progress 1

I think that this project is going to take me some time … there are some bits of information that I need to gather before I can really do very much, some case modifications and some decisions about how I go about providing connections to the power outputs.

I have been given an Antec SmartPower 2.0 500W power supply with dual “pull through” cooling fans. The power supply seems to have all that I need (and some redundant bits that I need to plan how to handle).

I downloaded the manual from the Antec website and it seems to have most of the information that I need … so far.

My requirements are:

- Break out connections for 3.3v, 5v and 12v;

- Switch between 12V and variable power output;

- voltmeter display to show voltage output on 12V/variable;

- 5V USB output;

- LED power indicator;

- LED standby indicator.

To achieve the 12V/Variable I plan to put in a SPDT toggle switch to select either 12V or Variable. When the 12V/Variable is in either state, for the voltage to be displayed on a voltmeter. This means that I’m going to have to dedicate one of the 5V outputs to power the voltmeter.

The 5V USB should be fairly straight forward, I just need to connect the outer two pins on the USB connection block to 5V and GND (the right way around).

I could embed the power supply inside a purpose built case that simply connects the power supply 20+4 connector into a compatible PCB connector and then break the connections out from that. That would also mean that, should I need to change the power supply later, that it is independent of the case and breakouts.

Anyway, I’m going to do some research and mull over the options before I do anything else with this project.

Friday, 31 October 2014

ATTiny85 Tutorials

I thought that it may be easier for everyone if I put together a single page that lists all of the ATTiny85 tutorials on this blog so that you can come here and launch off to the tutorial that you want to see.

Once again, these are based on the Freetronics Eleven tutorials that you get when you buy the Experimenters Kit.

My goal is to produce an ATTiny85 equivalent for each of the tutorials in that guide, so that you can take advantage of both the Freetronics basic tutorials and my experimentations with the ATTiny85.

I am a hobbyist, not an expert!

Tutorials

| Freetronics Tutorial | Comments |

| 01 – Controlling an LED | |

| 02 – Controlling 8 LED | 4 LED |

| 03 – Reading Digital (On/Off) Input | 4 LED |

| 04 – Reading Analog (Variable) Input | |

| 05 – Dimming LED Using PWM | |

| 06 – Making Things Move With Servos | |

| 07 – RGB LED | |

| 08 – Drive More Outputs With A Shift Register | 8 LED using 75HC595 |

| 09 – Making Sounds | Using alternative tone() function |

| 10 – Detecting Vibrations and Knocks | |

| 11 – Light Input Controlling Sound Output |

I’m going to come back to this article and fill in the blanks as I complete the tutorials, so check in from time to time to see how we get along.

I will include the Arduino sketch along with the article so that you can see how the code differs between the chips. I am still planning on doing the same with the ATTiny84 and I’m likely to use the same format.

Typically, the tutorials will include a pin assignment section, an image or video of the completed circuit, the Arduino code and some commentary on the differences that I’ve encountered and the approach that I’ve taken.

Thursday, 30 October 2014

ATTiny85 Tutorial 4 – Reading Analog (Variable) Input

This is the 4th tutorial in the Freetronics Experimenters Kit converted to ATTiny85.

With this tutorial, the main changes from the original tutorial is again the pin assignments. But, also, the ATTiny85 is not connected to the PC via the USB cable, so Serial.begin, Serial.print and Serial.println are redundant. I have removed them from the sketch.

In this tutorial, the light sensor is connected to first Analog Digital Comparator pin (physical pin 7 ADC1). In your sketch, the analog pins are A1, A2 and A3 … so for the purpose of this tutorial, we’re using A1. The LED is connected on pin 0 … got that, A1 and 0 … right, let’s move on.

The modified sketch is as follows.

int led = 0;

int lightLevel;

void setup()

{

pinMode(led, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

lightLevel = analogRead(A1);

digitalWrite(led, HIGH);

delay(lightLevel);

digitalWrite(led, LOW);

delay(lightLevel);

}

Within the loop function, the ATTiny85 reads the value of the light sensor, this gives a value of 0 – 5V. The value is read as an integer value from 0 – 1023. This value is assigned to the lightLevel variable that is used to set the blink rate of the LED. The more light there is, the slower the blink rate.

The yellow wire connects the light sensor to A1 on the ATTiny85 and the LED is connected to 0 on the ATTiny85.

To test this circuit, I powered it up and then turned on my LED lamp above the sensor … as you would expect, the blink rate slowed down, then I swung the lamp away from the sensor to give an analog light variation and the blink rate sped up as less light was hitting the sensor … all working as you would expect.

Again, I programmed the ATTiny85 using my ATTiny85 ICSP and powered the breadboard using my 5V power regulator.

That’ll do for now, I’ll come back to these tutorials next week.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

ATTiny85 Tutorial 8 – Drive More Outputs With A Shift Register

For this tutorial, I have tried to fit all of the components onto a half+ board. Of course, I’m using my 5V regulator, so I am cheating slightly. However, the ATTiny85 and the 74HC595 both fit on the board along with the required 8 LED.

The original Arduino sketch includes the instantiation of Serial communication, that hasn’t been enabled on my ATTiny85, so I’m just commenting it out in the sketch. I am also omitting the smoothing capacitor between data and GND, if you want to include it, by all means, knock yourself out.

The shift register tutorial uses only digital pins in the original, so I am substituting like for like in the ATTiny85 platform.

The wiring is a little confusing (probably because I crammed it all into a half+ board), but there really isn’t much to it.

So long as you get the connections between the ATTiny85 and the 74HC595, then it’s really just a matter of poke and play (of course, you’ll need to be careful with the Vcc and GND connections!).

I’ve taken the liberty of changing the sketch to something closer to what I’ll actually be using, so beware that there are some functional changes (although very few).

Onto the sketch:

/*

Shift Register Example

Turning on the outputs of a 74HC595 using an array.

Modified for ATTiny85

Hardware:

* 74HC595 shift register

* ATTiny85

* LEDs attached to each of the outputs of the shift register

*/

//Pin connected to ST_CP (12) of 74HC595

int latchPin = 2;

//Pin connected to SH_CP (11) of 74HC595

int clockPin = 3;

////Pin connected to DS (14) of 74HC595

int dataPin = 0;

//holders for information you're going to pass to shifting function

byte data;

byte chaseArray[8];

void setup() {

//set pins to output because they are addressed in the main loop

pinMode(latchPin, OUTPUT);

// Serial.begin(9600);

chaseArray[0] = 1; //00000001

chaseArray[1] = 2; //00000010

chaseArray[2] = 4; //00000100

chaseArray[3] = 8; //00001000

chaseArray[4] = 16; //00010000

chaseArray[5] = 32; //00100000

chaseArray[6] = 64; //01000000

chaseArray[7] = 128; //10000000

//function that blinks all the LEDs

//gets passed the number of blinks and the pause time

blinkAll_2Bytes(2, 500);

}

void loop() {

for (int j = 0; j < 8; j++) {

//load the light sequence you want from array

data = chaseArray[j];

//ground latchPin and hold low for as long as you are transmitting

digitalWrite(latchPin, 0);

//move 'em out

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, data);

//return the latch pin high to signal chip that it

//no longer needs to listen for information

digitalWrite(latchPin, 1);

delay(60);

}

}

// the heart of the program

void shiftOut(int myDataPin, int myClockPin, byte myDataOut) {

// This shifts 8 bits out MSB first,

//on the rising edge of the clock,

//clock idles low

//internal function setup

int i=0;

int pinState;

pinMode(myClockPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(myDataPin, OUTPUT);

//clear everything out just in case to

//prepare shift register for bit shifting

digitalWrite(myDataPin, 0);

digitalWrite(myClockPin, 0);

//for each bit in the byte myDataOut

//NOTICE THAT WE ARE COUNTING DOWN in our for loop

//This means that 000001 or "1" will go through such

//that it will be pin Q0 that lights.

for (i=7; i>=0; i--) {

digitalWrite(myClockPin, 0);

//if the value passed to myDataOut and a bitmask result

// true then... so if we are at i=6 and our value is

// %11010100 it would the code compares it to %01000000

// and proceeds to set pinState to 1.

if ( myDataOut & (1<<i) ) {

pinState= 1;

}

else {

pinState= 0;

}

//Sets the pin to HIGH or LOW depending on pinState

digitalWrite(myDataPin, pinState);

//register shifts bits on upstroke of clock pin

digitalWrite(myClockPin, 1);

//zero the data pin after shift to prevent bleed through

digitalWrite(myDataPin, 0);

}

//stop shifting

digitalWrite(myClockPin, 0);

}

//blinks the whole register based on the number of times you want to

//blink "n" and the pause between them "d"

//starts with a moment of darkness to make sure the first blink

//has its full visual effect.

void blinkAll_2Bytes(int n, int d) {

digitalWrite(latchPin, 0);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 0);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 0);

digitalWrite(latchPin, 1);

delay(200);

for (int x = 0; x < n; x++) {

digitalWrite(latchPin, 0);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 255);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 255);

digitalWrite(latchPin, 1);

delay(d);

digitalWrite(latchPin, 0);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 0);

shiftOut(dataPin, clockPin, 0);

digitalWrite(latchPin, 1);

delay(d);

}

}

I thoroughly recommend that you do this tutorial on the Arduino first before attempting the ATTiny85 version, so that you know what to expect and how the connections work. Other than that, this makes a nice and tiny board project, now I need to play with laying this out on a board so that I can etch it … that should be fun.

The above video is the ATTiny85 and 75HC595 sub board connected to breadboarded LED. This is the next step on from the breadboard version in this article, but uses the same sketch and is functionally identical.

Check out the rest of the tutorials here.

Monday, 27 October 2014

ATX Lab Power Supply – Plan

Well, my next project is a more reliable power supply for my bench. So far, I’ve managed my power needs by using a 9V battery, a 5V USB cable that I modified, or a AC power adaptor.

That’s been fine, to a point, but it doesn’t really give me the power that I need to supply multiple projects, plus, I’m forever having to set the power up to connect to my projects. I’ve made a couple of USB power cables and modified a couple of AC power adaptors that have the right DC power output, but I guess I want to go further.

I will be acquiring an old ATX PC power supply unit that I plan to modify to provide me with 3.3V, 5V, 12V and a variable power supply. The 3.3V, 5V and 12V will really just be a matter of minor modification to the ATX power supply. I intend to use an LM317 to build a variable supply from one of the 12V outputs on the ATX.

I’ll also build a new case for the power supply so that it both looks decent and is a bit safer. I don’t want to have an ugly and dangerous power supply on my desk, my darling wife would, most likely, object (truth is … so would I).

When I have the ATX, I’ll go ahead and void the warranty so that I can see how many of which value supplies I have to play with. I’ll also go through some testing to make sure that the on board supplies do what it says on the box.

According to Pinouts R U and Help With PCS the 20 pin Molex connection provides the following:

3 x 3.3V, 5 x 5V and 1 x 12V. There are some other connections (like ground, power OK, and power on). I can use the 3.3V and 5V as they are, but I’ll need to do something with the 12V so that I can get 12V as well as 1.25V – 11V (I think … there is some power drop across the LM317, so I’ll need to test that).

I think that what I can do is provide a SPDT switch on the 12V rail to either give me 12V or power through the LM317. Ideally, I’ll need a voltmeter on the adjustable power rail so that I can see what power I’m dialling in.

The 12V rail will go out to the LM317 with a potentiometer and voltmeter. I will keep the cooling fan in the build so that power that is dissipated as heat can be managed.

I’ll drill a few holes in the front to put in some banana plug connectors through the case.

I’ve found some pretty nice designs online so far, so I’ll be able to simplify my design process somewhat.

Anyway, that’s the plan so far. I’ll follow up when I have the ATX and I’ll make sure that I record the discovery and design phases.

Monday, 20 October 2014

AC Adaptor Power Supply – Acrylic Enclosure

This weekend I made an enclosure for my AC Adaptor. The requirements were pretty simple … make an enclosure that has holes for the power switch, potentiometer, input wires, output wires and for the nuts to anchor it to the base.

I also wanted the enclosure to be clear so that the LED power indictor would make the device light up when it was powered … I didn’t want to have to look for a single 5mm LED on a black enclosure, so I decided that it would be a good idea to make it from clear acrylic. It would also add to a 70’s kind of vibe, a.la. “Orac” from Blake’s 7.

Another reason that I thought that a clear enclosure would be good was that I had spent some time and effort in making the simple breadboard design uncluttered and “pure”, and I didn’t want to hide the electronics away from the world. It is what it is, and there is a certain aesthetic appeal.

So, with that in mind, I went and (carefully) hacked up some 5mm clear acrylic sheet. I did the rip sawing of the sheet using a jigsaw with a hacksaw blade (24 TPI – teeth per inch). I made a guide from a straight piece of pine that I had lying around and this gave me a piece that was about 10cm x 80cm. I then cut the work piece using a chop saw. I got some chip-out on the cuts with the chop saw because the blade was just a standard timber blade with 3 TPI. I’ll be getting a higher TPI blade for the chop saw when I can afford it.

After cutting the sides, base and lid, I then measured out where the holes should be, and the diameter of the holes. The Potentiometer needed a 6mm hole, the switch needed a 5mm hole and the holes for the wires and nuts were all 3mm.

Then i had to cut another top and another face piece because I had not accounted for the height of the breadboard inside the case (d’oh!). The breadboard sits on 4x12mm threaded nylon standoff spacers … I forgot the 4mm of nut that came through the bottom of the standoff.

I used an general purpose Tarzan’s Grip glue (the kind you use for gluing plastic models together). This kind of glue melts the plastic pieces together and forms a weld. You don’t want to use a cyanoacrylate (superglue) because:

- It doesn’t glue the pieces together well enough and

- It causes “ghosting” on the plastic … kind of a white smut on the surface that is very difficult to get off.

I then used some acetone to clean up the joints. You need to use some care with acetone in this case because it can also cause some ghosting and because breathing in the fumes is toxic. I dipped a cotton bud into the acetone and then rubbed the joints vigorously.

Then I sanded the edges until I was happy with the surface … I could have sanded more and I could have gone to a higher grit (I only went as high as a 600 grit). I didn’t want the joints to be invisible as I wanted them to catch some of the glow from the LED. This was going to highlight the edges and make them more of a feature.

Here is the end result.

With the power turned off … and

With the power turned on.

At the moment, the top is just sitting on the enclosure. I want to make some acrylic hinges from some cut-off pieces so that the enclosure is all one piece.

The only real downside to using clear acrylic for the enclosure is that it shows up fingerprints very well … and I don’t want to keep cleaning it.

The next thing that I want to make for this is the bending jig for the heating element so that I can actually use it to bend acrylic. Well … that’s a project for later.

NOTE: After using this circuit with a 12V Adaptor, the potentiometer started smoking, so I would NOT recommend that you use it for anything beyond 9V. For 12V, you would need a higher resistance potentiometer at least.

Further Note: After more investigation, this is entirely the wrong approach for building a variable voltage supply. I’m now going to start looking at building one based on an LM317 transistor.

Thursday, 16 October 2014

AC Adaptor Power Supply – Recycle – Part 2

CAUTION: Modification of AC Power Adaptors is potentially dangerous. Read the specifications on the adaptor and observe output and polarity. Mistakes with AC Power can kill you. If you are unsure of the specifications of the adaptor that you are tinkering with … throw it away and get one that you know. Do not do ANY soldering on the adaptor or it’s cable when the adaptor is plugged in. I take NO responsibility for your safety, that’s your job.

Okay, so I’ve repeated the safety warning … I’ve completed the breadboard edition of the circuit and, honestly, this is enough. I don’t need to make a PCB for this at all.

This is the top view of the supply. The power comes in from the left (at the moment it is connected to a 9V NiMH battery, but I intend to connect it to a 9V AC Adaptor). You can see the layout, it’s pretty straight forward.

This view shows the arrangement more clearly. I have spaced everything to fit on a 50 mm x 70 mm prototype board. It could be smaller, but it really doesn’t need to be.

I’ve pad soldered the components and used the component legs to bridge. It’s a pretty tidy solder job and I’m pleased with that aspect of the build.

When the SPDT switch is thrown, the LED lights up to indicate that there is power running through the circuit.

When I built this on the solderless breadboard, I had the unattached SPDT pin connected to GND and another indicator LED connected to the wiper (Leg 2) of the potentiometer. There was also a connection from Leg 1 to GND in t he solderless breadboard version. When it was running, the 9V battery was getting very hot, so I decided to cut these elements from the circuit rather than try to work it out (I know, sometimes I’m lazy) … I figured that there was re-routed power going back to the terminal block (and on to the 9V battery). I was going to look at putting in an IN4001 diode to protect the power source … not sure if that would have any benefit, but I’ll re-breadboard it at some later date and report back and improve the circuit.

I probably should connect Leg 1 on the potentiometer to ground via a resistor, but what the hay … this configuration works out just fine. There isn’t much variation in the power output when you spin the dial though. With a charged 9V battery I get 8.9V through to 8.1V when turning the pot.

I plan to make an enclosure out of acrylic sheet and using the circuit to supply power to a resistive wire for a heating element.

AC Adaptor Power Supply – Recycle

NOTE: This project was a bit of a failure … I’m redoing this project using an LM317 instead of just using a POT to try to adjust the power. If you follow this project, you will only end up with a pretty circuit that doesn’t do anything very useful.

CAUTION: Modification of AC Power Adaptors is potentially dangerous. Read the specifications on the adaptor and observe output and polarity. Mistakes with AC Power can kill you. If you are unsure of the specifications of the adaptor that you are tinkering with … throw it away and get one that you know. Do not do ANY soldering on the adaptor or it’s cable when the adaptor is plugged in. I take NO responsibility for your safety, that’s your job.

In my previous article on power supplies for electrolytic etching I made use of an old AC Adaptor (wall wart) to provide power via a switch and potentiometer to an anode and cathode used in a simple circuit to an electrolytic etching bath. The adaptor recycle can be used for other purposes, and in fact I made a polystyrene hot-wire cutter using this same circuit. Now that I’ve used the project in a couple of different “tools” I suppose that it’s time to revisit the design and see what can be improved or changed.

My new application for this project is in a tool that will be used to bend acrylic sheet. There are a couple of interesting articles that can be found on various sites scattered across the interweb. I’m not going to list any here, they change too often. You can look at sites like lifehack and instructables for some pretty good examples of polystyrene cutters. The power supply is really what I’m interested in, so I’m going to focus on that for now.

Essentially, the AC Adaptor power is passed through a circuit adding a switch to make it easier to turn the power on and off, and through a suitably resistant potentiometer to allow the user to adjust the output power, effectively controlling the heating element (or in the case of the electrolytic etcher, the copper electrolysis anode). It’s also a good idea to install a power indicator in the circuit to improve safety (a visual indicator that there is current passing through the circuits output terminals.

So, in my case, I’m using this supply for three tools and two different types.

- Heat:

- Polystyrene Hot Cutter;

- Acrylic Heat Bender; and

- Current:

- Electrolytic Etcher

So there is some versatility in the simple circuit.

The circuit above has two two pin screw terminal posts. The left-hand side is where the AC Adaptor will be connected to the circuit and the right-hand side is where the power will be output.

There are 6 parts (well 7 if you include the circuit board):

- 2 x 2 pin screw terminals;

- 1 x Red LED;

- 1 x 220Ω resistor;

- 1 x SPDT switch;

- 1 x B 10kΩ potentiometer (the resistance value of the pot should be increased to 100kΩ if you are using adaptors between >9 and 16V, I’m using a 9V adaptor, so 10kΩ … larger than that and you should probably not be using the adaptor at all).

I have connected the input power to a SPDT switch. This is where we turn the power to the output off. Of course, the power to the circuit is still live, you need to turn the wall socket off to completely power the circuit off.

The 3rd leg of the SPDT connects to the power indicator LED, which is connected to ground via a 220 ohm resistor. Additionally, the 3rd leg of the SPDT connects to the Power (leg 3) of the B10K potentiometer. The Wiper (leg 2) of the B10K potentiometer connects to the positive output terminal.

The negative input terminal connects to the resistor of the power indicator LED (as mentioned previously) and to the negative output terminal.

Connecting the load anode/cathode is done via the output terminal. I have a couple of banana plug to alligator clip connectors that I use, but bare wire end to spade connectors or any other appropriate connectors should be OK.

This is a good project candidate for mounting in a project box. I’m planning on bending some acrylic sheet to make the project box for this circuit … or you could make a pretty one by adding an instrument panel like my Steam Punk themed Electrolytic Etcher panel.

Tuesday, 14 October 2014

Prototype Embedded Electronics – Together

Now that I have completed the three circuits that I had planned to embed in the Steam Punk prop (Torch, Pulsing/Fading LED, LED Chaser) it’s time to put them together in a single main/sub configuration as they would be in the prop. I had to cheat a little here … I couldn’t find one of my male to male DuPont connectors and, rather than make a new one, I opted for the easier option of replacing the 2x2 SMD circuit with the 4 x 5 LED “Desk Light” circuit. In terms of testing the components together, this should really have no practical impact on the outcome. Sure, they are through hole components … and a lot more of them, so the only real difference from the perspective of testing the overall concept is that it will draw more power from the battery. In the embedded scenario, I need to rebuild ALL of the component circuits, so there really isn’t anything lost there.

I have connected a 9V battery to my trusty solderless breadboard and then connected each of the components to the power rails. The Torch and Pulsing/Fading circuits are connected to the 9V directly, whereas the LED Chaser is connected to 9V via a 5V Regulator (I opted for an early version of this as I didn’t need the optional LED power indicator).

The result is as expected … it all works just dandy. I should probably go ahead and work out power consumption so that I have an idea of how long the battery will last in the prop. I’m still toying with the idea of also embedding a battery charger circuit … but it is easy and cheap enough to use a commercial – “off the shelf” charger so I’m not going to bother with that … yet.

There are still more tweaks and optimisations that I am planning, but that’s for later.

I present to you the prototype embedded electronics of the Steam Punk prop …

Fiat Lux

DC Power Connector – Wiring and Testing

Last night I decided to repurpose an old 9V AC Adaptor for use in my electronics projects. The connector at the end was not suitable for my purposes, so I cut it off and soldered in a standard 2.1 x 5.5 barrel connector.

When I tested the power on the “completed” job, I noticed that I was getting none of the results that I was expecting.

Firstly, I was getting a negative value where I was expecting a positive, and secondly, the 9V that I was expecting … was showing 11.98V (let’s be gentle and say 12V). The AC Adaptor clearly shows that it is supposed to be 9V output … WFT? Also, the polarity symbol on the AC Adaptor shows that the sheath is supposed to be negative while the pole is supposed to be positive. I am annoyed (and rightly annoyed … with myself).

What I should have done was to perform some tests of the barrel connector first.

With the above diagram in mind, how can I test it? Simple …

Turn the multimeter on and switch it to continuity test.

Hold the black probe against the positive tab (that should be the short tab at the top in the diagram) and place the red probe into the positive inner jack. There should be a continuity buzz coming from he multimeter showing that there is a continuous circuit. Just to be sure, change the position of the red probe to the outer sheath of the barrel. There should be no continuity, so no buzz from the multimeter.

Now hold the black probe against the negative tab (that should be the long tab with the crimp tabs) and place the red probe against the outer sheath of the barrel. This should result in a closed circuit … so … buzz. Again, test that the negative tab does not connect to the inner jack by moving the red probe to the positive jack. While the final step isn’t really necessary since you have already tested continuity of this path for the positive rail, it doesn’t hurt to check it twice.

This test should reveal the way that the tabs on the back of the plug are routed and you should now know where you are soldering to.

Testing the terminal is a bit more fiddly. The post at the back of the terminal should be the positive rail, while the post under the terminal should be negative. On a three post terminal, the post on the side should close when the plug is inserted into the terminal.

I only care about the positive and negative connections.

To test this (at the moment, I’m talking about continuity testing) you will need to test each post and connection independently. The difficulty here lies in the fact that the spring will be making contact with the post, creating a circuit. You need to slide a non-conductive strip between the post and the spring clip. Something like a toothpick should do the trick.

When this is done place the black probe against the back post of the terminal and touch the red probe to the post in the middle of the socket at the front of the terminal. You may need to use alligator clips to attach the black probe to the rear post so that you can turn the socket over and poke around inside it. When you have contact with both the rear post and the post inside the terminal, you should get a buzz. Move the red probe to the spring clip inside the plug hole. You should not get a buzz here.

Attach your black probe to the post underneath the terminal and go back to probing the post and the clip with the red probe. This time, you should get a buzz when probing the spring clip and no buzz when probing the post.

Remove the non-conductive spacer from the terminal.

Thirdly, test that the plug and socket circuits are good. To do this, plug the male connector into the female socket. With the black probe attached to the short tab of the connector, probe the rear post with the red probe. You should get a buzz. With the black probe attached to the long tab of the connector, probe the post underneath the terminal. Again … buzz. You will probably also get a buzz at this stage if you probe the side post of the terminal.

Now that you know the polarity of the socket, you can happily match that up with your circuit.

You should note that I’m talking from the perspective of normal polarity, some circuits and some installations have these reversed … and that’s OK. The important thing is that you know which pole is which when you are connecting it to your circuit.

The most common use for this kind of connector (for home users and hobbyists) is to connect a 9V battery to a circuit board.

Monday, 13 October 2014

ATTiny85 Shift Register – Sub Board Populated

This weekend I completed the preparation work on the LED Sub Board for the ATTiny85 Shift Register board.

The preparation work was simply cutting the board to shape and filing it down to make it round.

Tonight, I populated the board with the resistors (SMD 0805 120Ω), the pin headers and the 3mm blue LED. There really wasn’t much involved in this other than getting down and doing it. I could have made my live a little easier by spacing the pin headers more … but, you live and learn.

The trickiest part was soldering the SMD resistors. I did this by first clipping the resistor onto the board with a spring clip and soldering one side (the inside edge) and then going around and soldering the outside. After that, I soldered the pin headers and finally, the LED. I gave the board, LED and pins a test using the multimeter and found that the pin header for LED 2 was dry soldered, so I went over it again until I had a decent solder filet.

The top of the board looks pretty straight forward, nothing much to see.

This is still a prototype board, so I’m not terribly fussed. I’m happy with the shaping of the board, but, again, I could make my life easier by making this slightly larger. In the final version, I plan to have sockets instead of LED soldered to the board as the LED will be mounted on the inside of a Steam Punk prop … not held flat to a disc.

Well, as far as a prototype goes, I think I’m happy with the outcome. I’ve learned some useful stuff about this type of circuit and I can use what I’ve learned when I’m making the version that will mount inside the prop, such as the spacing of the pin headers and the spacing and size of the screw mounting holes.

This project will probably end up as wearable electronics, I plan to mount the sub-board in opaque resin and make a badge out of it. I’ll also decrease the delay interval in the Arduino sketch to run roughly double the speed.

Thursday, 9 October 2014

Testing Arduino Code

There are a couple of ways that you can test your Arduino code, not least of which is compiling your sketch and then uploading it to your microprocessor and making sure it runs OK … however, that doesn’t help in revealing any problems in the code.

If there are major problems then, sure, the IDE will whine and you’ll hear about it. But what if there’s a silent problem in your code that you can’t necessarily find sooner?

I’m currently looking at using a C language IDE (CodeLite) as a testing ground for my code. I haven’t gone too far yet, so there are likely to be some issues (for instance, the byte data type is missing in GCC … apparently, so I’m using the char data type instead).

My thinking is that I should be able to use the C IDE to reveal any problems in my code by sending the data that I want to monitor to stdout and use stepping to inspect the values and variables as it goes along.

Other things to consider … a standard C application starts with int main() rather than void setup() and you have to explicitly define and call the loop() function, oh there are other differences that I’m sure to find along the way, but for simply testing function blocks to make sure that the data that my function is sending (and to a lesser extent, the function structure and flow), can be inspected discretely.

Playing with my Shift Register code, I created the following main.c file

and then I ran the code …

showing that the values being passed are correct.

I can also create a couple of different functions that do the same so that I can then have a look at them from an efficiency, memory and timing perspective to decide on which way is the best for my application.

Anyway, it’s all learning, poking and prodding. I’m not sure how others approach testing their Arduino code … but then, I’m a software tester by profession.

Wednesday, 8 October 2014

ATTiny85 Shift Register – Main Board Populated

Tonight, I populated the main board for this project and made the necessary connecting wires. You can see the previous post at ATTiny85 Shift Register – Etched.

I started out by making the 9 DuPont Female to Female 1 Pin wires, 8 yellow and 1 black. The yellow wires connect Q1 – Q8 on the shift register to (ultimately) LED 1 – LED 8 on the sub-board. This was mostly a process that took time. I cut the wires to 100mm, stripped 5mm from both ends of the wire, tinned the wires, tinned the DuPont connectors, soldered the wire to the DuPont connectors, slipped the pin housing onto the connector … job done. Although, 9 wires with a little finessing ended up taking me about 45 minutes to complete, I’m glad that job is done.

The next task was to populate the Main Board with the 8 and 16 pin DIP and the pin headers … there aren’t any heat sensitive components here, so it was, again, just a process.

Tested the board and connections with the multimeter, all happy.

After that, dropped in the ATTiny85 and 74HC595

I still have to pull the ATTiny85 and upload the modified Shift Register sketch onto it. I plan to test the main board by connecting it to 8 LED and resistors on a solderless breadboard. But … I’m too lazy and I think that I’ve done enough tinkering today.

huh … what do you know … I’m not that lazy!

Paypal Donations

Donations to help me to keep up the lunacy are greatly appreciated, but NOT mandatory.

![Power Supply - 01_thumb[1] Power Supply - 01_thumb[1]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-s5qZlYYWzcQ/VD9vBQ-leiI/AAAAAAAAGWw/qQnDAE39w00/Power%252520Supply%252520-%25252001_thumb%25255B1%25255D_thumb.jpg?imgmax=800)